Time for a Reassessment

When I started writing these “notes about Vietnam,” I suggested that changes in my own thoughts about the war sprang from the things I was writing about here. I think, now that I am past mid-year, through the Tet Offensive, having dealt with places I never went and never in my worst nightmares want to go: Hue, Lang Vei and Khe Sanh, that I ought to do some kind of self-assessment, see if I’ve really written about what caused my change.

Change? Where was I mentally and politically when I got my draft notice and decided to join up instead of let myself be dragged into the Army? Where was I a year and a half later when I boarded the USS Gordon and sailed from Oakland Bay to DaNang Harbor and then trans-shipped onto an LST to sail down the coast of what was then South Vietnam to the beaches of Chu Lai?

This I know: I was apolitical. I did not want to go to war, but I was neither for nor against that same war I did not want to participate in. I went because. . . ,well, because I went. I had no moral or political qualms about going; instead, like Dick Cheney, I would have preferred to be doing something else: skiing, fishing, whatever. But I did go.

Have you seen the film Go Tell the Spartans? It’s based upon a novel called Incident at Muc Wa by, if I remember correctly, Daniel Ford, and it was published back in March, 1967 (I looked that up and, yes, the author was Daniel Ford). That’s while I was already in the Army, stationed at Fort Hood with the 198th Light Infantry Brigade, preparing to go to Vietnam. The central character in the novel is a lot like I was at that time (though he was, fictively, in Vietnam in 1964, before the big buildup that got me drafted in 1965). A lot like me? He didn’t have political views of the war, went because, well, because, why not? His commander claims he’s a “war tourist”—went to see what it was like.

Let me confess, that, even now, I am not sorry I went. I learned a lot and what I learned has made me a different person than I would have been had I not gone. I can’t help but wonder if I would have been so much opposed to the first of the Persian Gulf Wars had I not been in Vietnam or to the second Iraq War and to the travesty we now have going on in Afghanistan—that whole litany of unnecessary wars and killings we have been engaged in during and after Vietnam.

But why turn against the Vietnam War while I was active in the war itself? All of the earlier blog entries I’ve written (27 already!) speak, indirectly, to that. If some of us participate remotely in a killing machine, even when we do not pull triggers, and if we neither believe in nor fail to believe in what we are doing, we do start asking ourselves why. You witness the destruction, even if you do not see the body, of a young man on a hill over-looking your camp; you meet the “enemy”—a 15 or 16 year old boy with a head injury who you are expected to interrogate—and the face of the “enemy” becomes visible. You see wounded children in the streets, men and women with no legs, with horrible burns…you see legions of women who have become prostitutes to survive and sell themselves to people in your company...you see people you are supposed to be helping not really wanting to, not really, be helped, not caring one way or the other if the current regime controls their lives or another regime, even if it’s communist, people who just want to be left alone.

You start wondering why you and the military you are a part of are there in the first place. Is it to defend what seems to be a fairly corrupt regime? Is it because we really, truly, believe that if we don’t stop them here, they’ll be invading us through California’s beaches just as we rushed down from the LSTs onto their beaches at Chu Lai? Is it because we truly believed that if Vietnam fell, Cambodia and Laos and Thailand would fall, maybe the Philippines? Dominoes keep clicking in my head! People in the military really are not supposed to think for themselves. That’s knocked out of them in basic training. They are supposed to obey orders. . .straight on up the chain of command: the platoon commander, the company commander, the battalion commander, the regimental commander, the division commander, the army commander, the MACV commander, the joint chiefs, the president…. Well, no. You can't do that. That leads to My Lai. That leads to mindless killing. We should always think before we kill. . .given enough time to do so.

Some people did not have that problem, perhaps most people. They believed and still do, absolutely, that we should have been there. They were not troubled by why we went to war, but they might well have been troubled by why we got out of the war when it was still going on. That’s okay. I mean, they start with different assumptions, with different beliefs, and that’s their business. I don’t argue with them, not ever, because when two people start off with different a priori assumptions, there’s no common meeting ground, no room for discussion, only for shouting. In Vietnam, yes, in Vietnam, I started, naively, with no assumptions at all. Oh, I had a vague sense that my country would not send me to a war without having a good reason to do so. I think now and thought before my war year was over that that basic assumption was wrong.

So, why were we there anyway? A game with the Soviets? That seems to be the best guess. We were there because we did not one foot of soil to fall to communism. The soviets had beaten us into space with Sputnik. . .Barack Obama’s Sputnik Moment for the other side, the URsputnik moment. We had lost the Bay of Pigs. They had backed down on the Cuban Missile Crisis. A chess game: and I was one of the pawns. All of us who went, regardless of our assumptions, were caught up in a huge game of global politics, a game that ate us up and spat us out. Things that were, to me at least, ultimately merely games countries play.

What happened that had any relevant affect on the United States when we quit and went home? Nothing I can think of.

But really, I changed because of the people I met there and people I did not meet but saw in the streets of Pleiku. And people I didn’t see in person, but saw on television and read about in the newspaper. Not peace movement people in the United States, but people like Thích Quảng Đức, the Buddhist monk who immolated himself to protest the war; people like General Loan, who put a pistol to the head of a prisoner and shot him; and so many people in Pleiku who were maimed, prostituted, desolate. It’s all so facile, so easy to say, but you think about things when you’re on guard duty, when you’re off work and town is closed down, when you’re squeezed into the back of a triLambretta with ten Vietnamese who are just people like you, when the Vietnamese woman who cleans your clothes and your hootch, works silently one day and the next and the next for a full year and then cries and, when you ask her why, just looks at you and then leaves.

I am not at all sure I can explain why I turned against a war I had been apathetic about, but when my friend Allen called me from Fort Bragg one day in the summer of 1969 and said “Come down to Fayetteville, we’re going to march against the war,” I packed my VW convertible and Don Mohr, my friend, joined me as we drove down to North Carolina to march with GIs United Against the War.

I’m not yet through with these blog entries, but needed to stop here for a moment, just to clarify some things in my own mind. My change was not Pauline (I did not get struck by a blinding light and hear God calling me out as Paul did); it was more Augustinian: the result of reading books from the small Air Force Library, of reading with open eyes the books I had taken to Vietnam with me, of seeing what we had done to a small country that had once been beautiful, of meeting our English students, of talking with prostitutes and children in the streets of Pleiku, of chatting over hot tea with an old woman who ran a tea shop, of coming to terms slowly and finding out, discovering, what I really believed and, yes, as corny as it sounds, who I really am.

Friday, February 11, 2011

Thursday, February 10, 2011

Just a Few Notes About Vietnam (Part 27)

After Tet

After Tet, time passed. It has a habit of doing that. We followed the news of the Marines and ARVN fighting to retake the City of Hue, the loss of life in attacking the Citadel, the discovery of mass graves and possible massacres of civilians by the VC. And we continued to watch the Siege of Khe Sanh on our Day Room television and wonder what the enemy was up to.

Did they really want to turn Khe Sanh into a second Dien Bien Phu? Didn’t they know they could not do that against a super-power like the United States. And yet, they tweaked us, dropped rockets and mortars on the base, defied the power arrayed against them. Starting with the battle at Dak To and moving through the hill fights, the VC, sometimes the PAVN, had been fighting almost constantly. Khe Sanh was the most protracted fight of them all.

It began prior to the Tet Offensive, on January 21, 1968, and lasted far past the offensive, finally, ending on April 8, 1978. That’s 3½ months of rockets and mortars falling on the camp. The Air Force had launched Operation Niagara, which dropped tons and tons of bombs around Khe Sanh, but enemy forces continued to attack. The severity of the American response was unmatched for ferocity.

According to Wikipedia, quoting authoritative sources:

By the end of the battle of Khe Sanh, U.S. Air Force assets had flown 9,691 tactical sorties and dropped 14,223 tons of bombs on targets within the Khe Sanh area. Marine Corps aviators had flown 7,098 missions and released 17,015 tons. Naval aircrews, many of whom were redirected from Operation Rolling Thunder, strikes against North Vietnam, flew 5,337 sorties and dropped 7,941 tons of ordnance in the area.

That’s a total of more than 22,000 tons of bombs, not including artillery fire directed at NVA and VC forces.

Those of us at the 330th? We just watched it on TV (like other Americans back home in the States). We knew that LBJ would not tolerate the enemy over-running the base, that he had ordered the military in Vietnam to ensure that it did not fall into enemy hands. Finally, though, Khe Sanh just ended. Relief columns fought their way into the base and the enemy faded back into the hills and jungles…across the border into Laos, across the DMZ, wherever they faded to.

During the siege, in a lesser known operation, the NVA, using 12 tanks, totally devastated a Green Beret camp near Khe Sanh, the small base (manned by Bru Montagnards, some Civilian Irregular Defense Group folks, and 24 Green Berets)was called Lang Vei. Marine Colonel Loundes and his staff refused to implement their existing plan to relieve Lang Vei because they feared it was a PAVN trap. Loundes was supported in that decision by General Westmoreland and Marine General Cushman.

Lieutenant Colonel Ladd, commander of the 5th Special Forces Group, infuriated that his men were being left to die at Lang Vei, proposed that Green Berets go to Lang Vei in Marine Helicopters to relieve their men. Cushman continued to resist until Westmoreland ordered him to provide the choppers. The relief effort was a success and managed to rescue 11 of the 24 Green Berets. The rest had been killed.

The Marines at Khe Sanh managed to further distinguish themselves by not allowing the Gook “Bru” to enter Khe Sanh. They had to find their own way back to Laos. All of this information is Wikipedia information, but it is all footnoted. I’m sure there are other, more reasonable explanations for the Marine behavior.

Us? We were mostly bored. We had been proved correct in our assessment of what was going to happen at Tet. And our lives changed slightly. A few of us stopped going into town because the regulations changed: Instead of civilian clothes, we had to wear jungle fatigues…and: we had to carry our M-16s with us. In other words, we had to join the Army!!!! Aside from that, our school was dismantled. We had one last meeting with our students and signed documents attesting to their having graduated as “advanced intermediate speakers of English.” We hoped those letters would help them get jobs and keep them out of the ARVN.

We continued to translate documents, did our day-to-day work. Nothing exciting happened for a few months and that was not earth-shattering: well, the commander of the 330th did receive a letter from the Inspector General’s Office stating that reports had reached pretty high levels that there was a morale problem in the company and that he should report back on the situation. Furthermore, the IG suggested that that report should probably start with an interview with Specialist Allen Hallmark. That is really Allen’s story, so I’ll stick to my own take on what followed in a subsequent blog.

After Tet, time passed. It has a habit of doing that. We followed the news of the Marines and ARVN fighting to retake the City of Hue, the loss of life in attacking the Citadel, the discovery of mass graves and possible massacres of civilians by the VC. And we continued to watch the Siege of Khe Sanh on our Day Room television and wonder what the enemy was up to.

Did they really want to turn Khe Sanh into a second Dien Bien Phu? Didn’t they know they could not do that against a super-power like the United States. And yet, they tweaked us, dropped rockets and mortars on the base, defied the power arrayed against them. Starting with the battle at Dak To and moving through the hill fights, the VC, sometimes the PAVN, had been fighting almost constantly. Khe Sanh was the most protracted fight of them all.

It began prior to the Tet Offensive, on January 21, 1968, and lasted far past the offensive, finally, ending on April 8, 1978. That’s 3½ months of rockets and mortars falling on the camp. The Air Force had launched Operation Niagara, which dropped tons and tons of bombs around Khe Sanh, but enemy forces continued to attack. The severity of the American response was unmatched for ferocity.

According to Wikipedia, quoting authoritative sources:

By the end of the battle of Khe Sanh, U.S. Air Force assets had flown 9,691 tactical sorties and dropped 14,223 tons of bombs on targets within the Khe Sanh area. Marine Corps aviators had flown 7,098 missions and released 17,015 tons. Naval aircrews, many of whom were redirected from Operation Rolling Thunder, strikes against North Vietnam, flew 5,337 sorties and dropped 7,941 tons of ordnance in the area.

That’s a total of more than 22,000 tons of bombs, not including artillery fire directed at NVA and VC forces.

Those of us at the 330th? We just watched it on TV (like other Americans back home in the States). We knew that LBJ would not tolerate the enemy over-running the base, that he had ordered the military in Vietnam to ensure that it did not fall into enemy hands. Finally, though, Khe Sanh just ended. Relief columns fought their way into the base and the enemy faded back into the hills and jungles…across the border into Laos, across the DMZ, wherever they faded to.

During the siege, in a lesser known operation, the NVA, using 12 tanks, totally devastated a Green Beret camp near Khe Sanh, the small base (manned by Bru Montagnards, some Civilian Irregular Defense Group folks, and 24 Green Berets)was called Lang Vei. Marine Colonel Loundes and his staff refused to implement their existing plan to relieve Lang Vei because they feared it was a PAVN trap. Loundes was supported in that decision by General Westmoreland and Marine General Cushman.

Lieutenant Colonel Ladd, commander of the 5th Special Forces Group, infuriated that his men were being left to die at Lang Vei, proposed that Green Berets go to Lang Vei in Marine Helicopters to relieve their men. Cushman continued to resist until Westmoreland ordered him to provide the choppers. The relief effort was a success and managed to rescue 11 of the 24 Green Berets. The rest had been killed.

The Marines at Khe Sanh managed to further distinguish themselves by not allowing the Gook “Bru” to enter Khe Sanh. They had to find their own way back to Laos. All of this information is Wikipedia information, but it is all footnoted. I’m sure there are other, more reasonable explanations for the Marine behavior.

Us? We were mostly bored. We had been proved correct in our assessment of what was going to happen at Tet. And our lives changed slightly. A few of us stopped going into town because the regulations changed: Instead of civilian clothes, we had to wear jungle fatigues…and: we had to carry our M-16s with us. In other words, we had to join the Army!!!! Aside from that, our school was dismantled. We had one last meeting with our students and signed documents attesting to their having graduated as “advanced intermediate speakers of English.” We hoped those letters would help them get jobs and keep them out of the ARVN.

We continued to translate documents, did our day-to-day work. Nothing exciting happened for a few months and that was not earth-shattering: well, the commander of the 330th did receive a letter from the Inspector General’s Office stating that reports had reached pretty high levels that there was a morale problem in the company and that he should report back on the situation. Furthermore, the IG suggested that that report should probably start with an interview with Specialist Allen Hallmark. That is really Allen’s story, so I’ll stick to my own take on what followed in a subsequent blog.

Tuesday, February 8, 2011

Just a Few Notes About Vietnam (Part 26)

Witness, not a participant, to Tet, 1968

So, a few days before Tet. As I recall, Allen’s parents were vacationing in Thailand and Allen was on a week or two leave to visit them in the Bangkok area. I always thought Ms. Hallmark had intelligence operatives that were somewhat better than the CIA’s and managed to get her oldest son out Vietnam for Tet, but je ne sais quoi! I could, quite easily, be misremembering this whole thing and I’ll rely on Allen to set the record straight.

We did work really hard in those days: translating, putting things together, sending reports out whenever some little VC sitting somewhere in the South sent a message indicating that his unit was ready for the forthcoming great and glorious offensive and general uprising. We heard rumors that the Pleiku Provincial Chief and his family had left for Saigon for classier Tet parties than could be found on a provincial backwater like Pleiku…but those were just rumors. As it was, Pleiku had a rather exciting Tet party of its own…not, however, rivaling that held in either Saigon or the imperial city of Hue.

The night of the Eve of Tet, 1968, the 330th was on alert as everyone in all of South Vietnam really, really, really should have been. I recall starting out in the bunker (might as well be safe) and drinking a few '33' beers before migrating to the berm. A few VC units had jumped the gun, so to speak, and started their offensive a little early, but I suspect that had just caused MACV to think their attack was the whole thing, easily overcome.

I still recall how creepy it all seemed that night. Remember: our company was between the Cambodia border and the town of Pleiku, 4th Division HQ was on the other side of the town. To get to the city, the VC had to march around us. That night I listened carefully, tried to hear any sign of thousands of enemy troops marching past us but could never hear anything. They must have stayed a klick or two north and south of the areas our floodlights highlighted.

Finally, I hear the sounds of a huge firefight, see tracers—green for the bad guys, red for us good guys. I see flashes, hear explosions from down in the city, dark night, flashing lights. Amber flares shoot up in an explosion of artillery and drift down beneath white parachutes. The rest of the 330th races to the berm, poised to return fire that never comes. The Tet Offensive of 1968 is not about American bases; it is, instead, an attempt to take control of all the major town and cities in the South. In direct disobedience to General William C. Westmoreland, the VC demonstrate that they can, indeed, wage war all over the country on the same freaking night!

The VC hold out, stay in Pleiku for two days. They kill a number of people; we kill a number of people. That’s what this war is all about: numbers, not territory taken and held, not old-style war. They keep control of Hue and its Citadel much longer. Marines and ARVN fight street to street in that city before they regain control. The best description I have read of the Hue fighting is in Michael Herr’s Dispatches and in Gustav Hasford's great novel, The Short-Timers (Full Metal Jacket was made from that book).

Our indigenous native personnel? The ones who work for us at the 330th? They had not come in to work the day before. I wonder why? Xuans 1 and 2? Our very own bar girls? MIA for three days. No one reports to work in the Mess Hall. The men who burn our shit? They had some compelling reason not to come to work that day before. Who needed intel? We could tell by the number of Vietnamese locals who showed up for work or who failed to show up.

The big news: Yes, we did win the Tet Offensive. The North and their southern minions failed to achieve any of their stated objectives. There was no general uprising. Well, they did manage to occupy a few towns for a few days. A few things spoiled that major victory for us: 1. the false notion that our embassy had been over-run, 2) television images of the fighting including General Loan’s execution of the VC soldier in civilian clothes, 3) General Westmoreland’s statements about enemy strength in the weeks prior to Tet.

The so-called “fog of war” was at its foggiest in those days during and after Tet, 1968. The VC ,after Tet, were closer to what the General had described before Tet: unable to mount another major battle. As a fighting force, they were wasted, destroyed during Tet. From Tet on, most of the fighting would be done by the North Vietnamese Army. We did win Tet, but we lost the war that week…even though we would continue to fight for five long years afterwards.

So, a few days before Tet. As I recall, Allen’s parents were vacationing in Thailand and Allen was on a week or two leave to visit them in the Bangkok area. I always thought Ms. Hallmark had intelligence operatives that were somewhat better than the CIA’s and managed to get her oldest son out Vietnam for Tet, but je ne sais quoi! I could, quite easily, be misremembering this whole thing and I’ll rely on Allen to set the record straight.

We did work really hard in those days: translating, putting things together, sending reports out whenever some little VC sitting somewhere in the South sent a message indicating that his unit was ready for the forthcoming great and glorious offensive and general uprising. We heard rumors that the Pleiku Provincial Chief and his family had left for Saigon for classier Tet parties than could be found on a provincial backwater like Pleiku…but those were just rumors. As it was, Pleiku had a rather exciting Tet party of its own…not, however, rivaling that held in either Saigon or the imperial city of Hue.

The night of the Eve of Tet, 1968, the 330th was on alert as everyone in all of South Vietnam really, really, really should have been. I recall starting out in the bunker (might as well be safe) and drinking a few '33' beers before migrating to the berm. A few VC units had jumped the gun, so to speak, and started their offensive a little early, but I suspect that had just caused MACV to think their attack was the whole thing, easily overcome.

I still recall how creepy it all seemed that night. Remember: our company was between the Cambodia border and the town of Pleiku, 4th Division HQ was on the other side of the town. To get to the city, the VC had to march around us. That night I listened carefully, tried to hear any sign of thousands of enemy troops marching past us but could never hear anything. They must have stayed a klick or two north and south of the areas our floodlights highlighted.

Finally, I hear the sounds of a huge firefight, see tracers—green for the bad guys, red for us good guys. I see flashes, hear explosions from down in the city, dark night, flashing lights. Amber flares shoot up in an explosion of artillery and drift down beneath white parachutes. The rest of the 330th races to the berm, poised to return fire that never comes. The Tet Offensive of 1968 is not about American bases; it is, instead, an attempt to take control of all the major town and cities in the South. In direct disobedience to General William C. Westmoreland, the VC demonstrate that they can, indeed, wage war all over the country on the same freaking night!

The VC hold out, stay in Pleiku for two days. They kill a number of people; we kill a number of people. That’s what this war is all about: numbers, not territory taken and held, not old-style war. They keep control of Hue and its Citadel much longer. Marines and ARVN fight street to street in that city before they regain control. The best description I have read of the Hue fighting is in Michael Herr’s Dispatches and in Gustav Hasford's great novel, The Short-Timers (Full Metal Jacket was made from that book).

Our indigenous native personnel? The ones who work for us at the 330th? They had not come in to work the day before. I wonder why? Xuans 1 and 2? Our very own bar girls? MIA for three days. No one reports to work in the Mess Hall. The men who burn our shit? They had some compelling reason not to come to work that day before. Who needed intel? We could tell by the number of Vietnamese locals who showed up for work or who failed to show up.

The big news: Yes, we did win the Tet Offensive. The North and their southern minions failed to achieve any of their stated objectives. There was no general uprising. Well, they did manage to occupy a few towns for a few days. A few things spoiled that major victory for us: 1. the false notion that our embassy had been over-run, 2) television images of the fighting including General Loan’s execution of the VC soldier in civilian clothes, 3) General Westmoreland’s statements about enemy strength in the weeks prior to Tet.

The so-called “fog of war” was at its foggiest in those days during and after Tet, 1968. The VC ,after Tet, were closer to what the General had described before Tet: unable to mount another major battle. As a fighting force, they were wasted, destroyed during Tet. From Tet on, most of the fighting would be done by the North Vietnamese Army. We did win Tet, but we lost the war that week…even though we would continue to fight for five long years afterwards.

Monday, February 7, 2011

Just a Few Notes About Vietnam (Part 25)

Interim: a Visit to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

I was in Washington last week and, as I usually do when I am in that city, took time to visit the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the Wall. And, as usual, I found myself tearing up. I visit out of respect for all those young men and a few women who gave their lives in our war. It does not really matter whether we approve of the country’s wars or not, the sacrifice deserves respect. Still, though, I had been reviewing Vivian Shipley’s recent collection of poems, All Your Memories Have Been Erased, just before I left for D.C. and could not help remembering her poem for the students killed at Virginia Tech and the haunting line about how they were cut off “mid-song.” The human beings represented by the names carved into that black wall were also only part way through singing their own songs when their voices were lost to us all.

I was rushed on this visit and took a taxi from the conference hotel to the memorial. The cabbie seemed used to Vietnam veterans rushing to the Wall and asked if I had been there, meaning Vietnam. When I said yes, he said he'd wait for me on the other side of the Lincoln Memorial. The area was totally under repair, reflecting pool drained, walkways rerouted, but the Wall...it still called out to people. The last time I was there a few kids were racing around and their parents were shushing them, asking them to behave. I remember telling them that the people represented by the names would not have minded, that that kind of happiness and joy was okay with them. This time, though, only a few of us, no cherry trees in bloom, no laughing children.

The first few times I visited The Wall, I did not feel that sense of healing some veterans have mentioned, instead. . . Well, I’ve written a few poems, none recently, about how the memorial makes me feel. The first was originally published in Valparaiso Poetry Review and was about a trip I took to the memorial with my friend Pat Valdata. Pat’s a glider pilot and writer and she was a good companion on that walk up the reflection pond to the Lincoln Memorial before we turned right to visit Maya Lin’s tribute:

New Names

1

Cherry blossoms blow along the ground

and green buds promise leaves to come,

closed walkways send us west and nothing's

mirrored in the murky pond.

She notes that gulls soar much as she does

when the clouds build just this way.

She paces me, stride for stride, sees

mallards, heads buried in the slime.

She seems entranced with winged things.

2

Here, the cherries blossom still—a little

north and east of where we stand.

The path leads down beside a polished wall

that sprouts the names of one war's dead.

New faces blossom, new letters grow

from black wings struggling to rise, but

anchored in the hill and in our minds.

New names to link old remains—men

and women who will not grow old.

The wings reflect, although the pond does not,

cherry blossoms in the April sun.

I have returned to the place many times in the intervening years and, each time, the memorial affects me in a different way. The image of “wings,” though: that is constant. When I last wrote about the memorial, I was thinking of the young man named Bao who reported on the camp at Dak To and about what was, surely, his own death after we had pinpointed his locations:

Not All the Names Are There

I said I would not write about the Wall,

two wings of black marble with 58,000 names.

I knew not all the names were there, not all.

They said the Wall brings healing, peace,

understanding. They never mentioned rage.

I knew I should not write about the Wall.

A boy named Bao lay dying on a hill,

his body burned with napalm, his death my call.

I knew not all the names were there, I could not

see his name and face behind the marble sheen

neither on the west nor on the east, no trace.

No one wrote his name upon the Wall.

No one ever mentioned tears could fall and rage

could dominate between those wings of black carved names.

I said I would not write about the Wall;

not all the names can fit there, hardly all.

This time, the visit brought regret. I think the truth about the Wall is that it does not simply reflect our faces against the carved names of the dead in the black mirror polish of its exterior, but also reflects the baggage we bring with us. This is Maya Lin’s real achievement: that the memorial is different for each man or woman who sees it, just as our war was different for each person who fought in it. We do not simply see their names, but see our whole lives since theirs were lost.

January 30, 1968, was neither warm nor cold in the area around Pleiku, but it was a day many new names would become eligible for the stone carver’s art. Allen, Jim, Will, all of us who worked in the linguist hootch at the 330th and all the cryppies, reporters, diddy-boppers, mechanics, cooks, all of us, knew the morning would change the course of the war and would, simultaneously, change dramatically, the way we would live out the remainder of our tour in Vietnam.

I was in Washington last week and, as I usually do when I am in that city, took time to visit the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the Wall. And, as usual, I found myself tearing up. I visit out of respect for all those young men and a few women who gave their lives in our war. It does not really matter whether we approve of the country’s wars or not, the sacrifice deserves respect. Still, though, I had been reviewing Vivian Shipley’s recent collection of poems, All Your Memories Have Been Erased, just before I left for D.C. and could not help remembering her poem for the students killed at Virginia Tech and the haunting line about how they were cut off “mid-song.” The human beings represented by the names carved into that black wall were also only part way through singing their own songs when their voices were lost to us all.

I was rushed on this visit and took a taxi from the conference hotel to the memorial. The cabbie seemed used to Vietnam veterans rushing to the Wall and asked if I had been there, meaning Vietnam. When I said yes, he said he'd wait for me on the other side of the Lincoln Memorial. The area was totally under repair, reflecting pool drained, walkways rerouted, but the Wall...it still called out to people. The last time I was there a few kids were racing around and their parents were shushing them, asking them to behave. I remember telling them that the people represented by the names would not have minded, that that kind of happiness and joy was okay with them. This time, though, only a few of us, no cherry trees in bloom, no laughing children.

The first few times I visited The Wall, I did not feel that sense of healing some veterans have mentioned, instead. . . Well, I’ve written a few poems, none recently, about how the memorial makes me feel. The first was originally published in Valparaiso Poetry Review and was about a trip I took to the memorial with my friend Pat Valdata. Pat’s a glider pilot and writer and she was a good companion on that walk up the reflection pond to the Lincoln Memorial before we turned right to visit Maya Lin’s tribute:

New Names

1

Cherry blossoms blow along the ground

and green buds promise leaves to come,

closed walkways send us west and nothing's

mirrored in the murky pond.

She notes that gulls soar much as she does

when the clouds build just this way.

She paces me, stride for stride, sees

mallards, heads buried in the slime.

She seems entranced with winged things.

2

Here, the cherries blossom still—a little

north and east of where we stand.

The path leads down beside a polished wall

that sprouts the names of one war's dead.

New faces blossom, new letters grow

from black wings struggling to rise, but

anchored in the hill and in our minds.

New names to link old remains—men

and women who will not grow old.

The wings reflect, although the pond does not,

cherry blossoms in the April sun.

I have returned to the place many times in the intervening years and, each time, the memorial affects me in a different way. The image of “wings,” though: that is constant. When I last wrote about the memorial, I was thinking of the young man named Bao who reported on the camp at Dak To and about what was, surely, his own death after we had pinpointed his locations:

Not All the Names Are There

I said I would not write about the Wall,

two wings of black marble with 58,000 names.

I knew not all the names were there, not all.

They said the Wall brings healing, peace,

understanding. They never mentioned rage.

I knew I should not write about the Wall.

A boy named Bao lay dying on a hill,

his body burned with napalm, his death my call.

I knew not all the names were there, I could not

see his name and face behind the marble sheen

neither on the west nor on the east, no trace.

No one wrote his name upon the Wall.

No one ever mentioned tears could fall and rage

could dominate between those wings of black carved names.

I said I would not write about the Wall;

not all the names can fit there, hardly all.

This time, the visit brought regret. I think the truth about the Wall is that it does not simply reflect our faces against the carved names of the dead in the black mirror polish of its exterior, but also reflects the baggage we bring with us. This is Maya Lin’s real achievement: that the memorial is different for each man or woman who sees it, just as our war was different for each person who fought in it. We do not simply see their names, but see our whole lives since theirs were lost.

January 30, 1968, was neither warm nor cold in the area around Pleiku, but it was a day many new names would become eligible for the stone carver’s art. Allen, Jim, Will, all of us who worked in the linguist hootch at the 330th and all the cryppies, reporters, diddy-boppers, mechanics, cooks, all of us, knew the morning would change the course of the war and would, simultaneously, change dramatically, the way we would live out the remainder of our tour in Vietnam.

Saturday, January 29, 2011

Just a Few Notes About Vietnam (Part 24)

Approaching Tet

It’s amazing how often miss-truths or someone’s personal opinion gets printed in newspapers. On Friday, General Patrick Brady, who received the MOH in Vietnam and whose service I honor, did an Op-Ed in the San Antonio Express-News. Most of his facts are, basically, correct; his conclusions are suspect.

General Brady writes The American soldier was never defeated on the battlefield in Vietnam; our defeat came from the elite in the courtrooms, the classroom, the cloakrooms and the newsrooms, from cowardly media-phobic politicians and irresponsible, dishonest media and professors from Berkeley to Harvard. This is old, hackneyed warmed-over crap. To start with, no, we did not win every battle in Vietnam. Several outposts were totally over-run by the NVA and/or the VC. Ipso facto: we did not win those battles.

Hamburger Hill? Yes, the enemy quit fighting and left. We left. Dak To? The enemy quit fighting and melted back across the borders into Cambodia and Laos. They came back. Khe Sanh? We won by enduring a shitload of rocket and mortar fire without getting all the Marines there killed? And then, the enemy stopped and left. Not exactly a victory at Khe Sanh, Not a loss, I guess, but certainly not a victory. You can't declare victory unless you know what the people attacking you want and that you kept them from achieving it.

But General Brady is right. The Americans and most of the ARVN fought well during the Tet Offensive and the North did not achieve any of the objectives it set for itself. A clear American victory. BUT…

Why did the media react the way they did? And let’s be clear about this, not many people in the media ever called TET an American loss. What seems to have happened back when Patrick Brady was a young man is that the MACV generals led by General William C. Westmoreland, only a short while before Tet 1968, had been boasting in news briefings that the VC were on the run and could not mount a credible offensive anywhere. The media duly repeated that on television and in newsprint. Is it any wonder that Walter Cronkite said “I thought we were winning this thing” when the VC rose up all over the country, attacked most of the cities, occupying many of them, and stayed in Hue for weeks after Tet?

If anyone caused the media reaction to Tet, it was General Westmoreland and his cadre of sycophantic, yesman generals.

And the assertion that history professors call Tet a military loss is patently absurd. They do, frequently, call it a public relations loss. That's absolutely correct.

Between Christmas and Tet at the 330th, we started translating message after message indicating that there was going to be an attack in Saigon, an attack in Tay Ninh, in Nha Trang, in Pleiku, in Kontum, in. . .well, every South Vietnamese city and town you can imagine. The messages even said when the attacks would take place: Tet, 1968. We were amazed: listening to MACV’s comments and reading messages from the NLF. There was a strange sort of disconnect here…someone was living in a fantasy world. We didn’t believe the first few translations we made, but as stuff poured in from all over the country, we became believers.

We sent reports and messages to MACV, to the White House, to every responsible official. Other intelligence units were sending similar messages. We were totally ignored because the generals followed their misguided beliefs of “VC on the RUN” instead of their intelligence units. In hindsight, the VC should not have attacked on Tet. They believed their own mythos, too: that the rest of the Vietnamese in the South would rise up and assist them. And so, they attacked. And they were killed in huge numbers. After Tet, what William Westmoreland had said before Tet was correct: they could no longer manage a credible offensive anywhere in the South. So, we won but not as decisively as we should have; we were not as well prepared as we should have been.

I sympathize with General Brady and appreciate his service. He’s obviously a true believer and speaks the truth "as he sees it," but true believers can't always see beyond their own preconceived notion of truth.

On the night of Tet, we retired to our palatial bunkers, but...that’s the subject for the next blog entry.

It’s amazing how often miss-truths or someone’s personal opinion gets printed in newspapers. On Friday, General Patrick Brady, who received the MOH in Vietnam and whose service I honor, did an Op-Ed in the San Antonio Express-News. Most of his facts are, basically, correct; his conclusions are suspect.

General Brady writes The American soldier was never defeated on the battlefield in Vietnam; our defeat came from the elite in the courtrooms, the classroom, the cloakrooms and the newsrooms, from cowardly media-phobic politicians and irresponsible, dishonest media and professors from Berkeley to Harvard. This is old, hackneyed warmed-over crap. To start with, no, we did not win every battle in Vietnam. Several outposts were totally over-run by the NVA and/or the VC. Ipso facto: we did not win those battles.

Hamburger Hill? Yes, the enemy quit fighting and left. We left. Dak To? The enemy quit fighting and melted back across the borders into Cambodia and Laos. They came back. Khe Sanh? We won by enduring a shitload of rocket and mortar fire without getting all the Marines there killed? And then, the enemy stopped and left. Not exactly a victory at Khe Sanh, Not a loss, I guess, but certainly not a victory. You can't declare victory unless you know what the people attacking you want and that you kept them from achieving it.

But General Brady is right. The Americans and most of the ARVN fought well during the Tet Offensive and the North did not achieve any of the objectives it set for itself. A clear American victory. BUT…

Why did the media react the way they did? And let’s be clear about this, not many people in the media ever called TET an American loss. What seems to have happened back when Patrick Brady was a young man is that the MACV generals led by General William C. Westmoreland, only a short while before Tet 1968, had been boasting in news briefings that the VC were on the run and could not mount a credible offensive anywhere. The media duly repeated that on television and in newsprint. Is it any wonder that Walter Cronkite said “I thought we were winning this thing” when the VC rose up all over the country, attacked most of the cities, occupying many of them, and stayed in Hue for weeks after Tet?

If anyone caused the media reaction to Tet, it was General Westmoreland and his cadre of sycophantic, yesman generals.

And the assertion that history professors call Tet a military loss is patently absurd. They do, frequently, call it a public relations loss. That's absolutely correct.

Between Christmas and Tet at the 330th, we started translating message after message indicating that there was going to be an attack in Saigon, an attack in Tay Ninh, in Nha Trang, in Pleiku, in Kontum, in. . .well, every South Vietnamese city and town you can imagine. The messages even said when the attacks would take place: Tet, 1968. We were amazed: listening to MACV’s comments and reading messages from the NLF. There was a strange sort of disconnect here…someone was living in a fantasy world. We didn’t believe the first few translations we made, but as stuff poured in from all over the country, we became believers.

We sent reports and messages to MACV, to the White House, to every responsible official. Other intelligence units were sending similar messages. We were totally ignored because the generals followed their misguided beliefs of “VC on the RUN” instead of their intelligence units. In hindsight, the VC should not have attacked on Tet. They believed their own mythos, too: that the rest of the Vietnamese in the South would rise up and assist them. And so, they attacked. And they were killed in huge numbers. After Tet, what William Westmoreland had said before Tet was correct: they could no longer manage a credible offensive anywhere in the South. So, we won but not as decisively as we should have; we were not as well prepared as we should have been.

I sympathize with General Brady and appreciate his service. He’s obviously a true believer and speaks the truth "as he sees it," but true believers can't always see beyond their own preconceived notion of truth.

On the night of Tet, we retired to our palatial bunkers, but...that’s the subject for the next blog entry.

Monday, January 24, 2011

Just a Few Notes about Vietnam (Part 23)

Between New Year's Day and Tết Nguyên Đán

I have been thinking about poetry while thinking about the time between the western New Year and Tết Nguyên Đán, Between January 1, 1968, and Tet, 1968. And, as with most of us, I have been thinking, always, at least a little, this week, about the economy, which I won’t talk about anymore. Unlike most of us, I have also been re-reading Bruce Weigl’s Song of Napalm this afternoon and I thought, well, yes, there it is. I, also, thought about what’s happening today and how I might have to put off retirement for five additional years (okay, I did talk about it again)...but poetry, poetry is about deeper concerns than this year’s economy or at least it is for me.

"Put off retirement." The phrase reminds me of the way we used to refer, and I regret this, pejoratively, to NCOs who were career men back in Vietnam: “Lifers” and “Beggars.” That was unkind of those of us who were tourists and draftees in the Army then and now seems even worse than unkind. Language, word choice, what we call a man or a thing, is always important. Poetry helps us think of words and word choice in new ways. I have been told (and were I a true scholar would look for the evidence) that the racist term “Gook”—much used on both the VC and our allies, the ARVN in Vietnam—actually comes from Korea.

There’s a story, of sorts, behind that: When the first ship bearing American soldiers landed in Korea, the Korean people on the docks shouted a phrase that sounded like “me Gook.” The Americans purportedly thought they were shouting “me Gook,” “I am a Gook,” and started calling them that. This is an absurd example of the reflexive and a bilingual joke since the Korean word for “American” sounds like “me Gook” and is similar to the Vietnamese word for the United States: “My Quoc.” Probably all of that is absurd and there is an even better reason.

Why absurd? Mostly because the Oxford English Dictionary traces the word back to 1935 in the Philippines:

“1935 Amer. Speech 10 79/1 Gook, anyone who speaks Spanish, particularly a Filipino.

“1947 N.Y. Herald Tribune 2 Apr. 28/6 The American troops‥don't like the Koreans—whom they prefer to call ‘Gooks’—and, in the main, they don't like Korea.”

Poetry. Poetry is essential stuff. Poetry makes us, takes us, helps us consider new places, new concepts, encourages us to revisit the condition of being human. Oh, it may make us laugh, may turn us from gloomy thoughts, but somehow, poetry takes us deep down into places we have never been have and perhaps never wanted to go, fills us with almost inexpressible joy or exposes us to a reality we might have preferred to avoid.

It is not always EASY because life is not always easy, and for the same reasons, it is not always pleasant; it does not fit on a Hallmark card. Weigl reminds me, whenever I read his poems, that sometimes the thickets of our lives are deep, dark and gloomy. Frost is right: “The woods ARE lovely / Dark and Deep” and, yes, “[we do] have promises to keep,” but Weigl forces us to realize that we should not ignore the Dark and Deep part of that beautiful poem, and that, yes, “The lie [hidden behind the beauty of the words] works only as long as it takes to speak / and the girl runs / only as far as the napalm allows.” I will not share more of Weigl’s poem except that “…Nothing / can change that, she is burned behind my eyes / and not your good love and not the rain-swept air / and not the jungle-green / pasture unfolding before us can deny it.”

I am, I suppose, avoiding writing about what happened between the two New Year’s days: ours and theirs. Nothing of what most people would consider “poetic” happened in those days. We worked, we slept, we taught at our little school, we hitched rides downtown or not. We were bored a whole lot. We kept up with the news. We read in the newspapers, saw on television, that General William C. Westmoreland thought the VC were in retreat, that they would be unable to mount any kind of sustained attack again. And we began to translate some odd messages.

I have been thinking about poetry while thinking about the time between the western New Year and Tết Nguyên Đán, Between January 1, 1968, and Tet, 1968. And, as with most of us, I have been thinking, always, at least a little, this week, about the economy, which I won’t talk about anymore. Unlike most of us, I have also been re-reading Bruce Weigl’s Song of Napalm this afternoon and I thought, well, yes, there it is. I, also, thought about what’s happening today and how I might have to put off retirement for five additional years (okay, I did talk about it again)...but poetry, poetry is about deeper concerns than this year’s economy or at least it is for me.

"Put off retirement." The phrase reminds me of the way we used to refer, and I regret this, pejoratively, to NCOs who were career men back in Vietnam: “Lifers” and “Beggars.” That was unkind of those of us who were tourists and draftees in the Army then and now seems even worse than unkind. Language, word choice, what we call a man or a thing, is always important. Poetry helps us think of words and word choice in new ways. I have been told (and were I a true scholar would look for the evidence) that the racist term “Gook”—much used on both the VC and our allies, the ARVN in Vietnam—actually comes from Korea.

There’s a story, of sorts, behind that: When the first ship bearing American soldiers landed in Korea, the Korean people on the docks shouted a phrase that sounded like “me Gook.” The Americans purportedly thought they were shouting “me Gook,” “I am a Gook,” and started calling them that. This is an absurd example of the reflexive and a bilingual joke since the Korean word for “American” sounds like “me Gook” and is similar to the Vietnamese word for the United States: “My Quoc.” Probably all of that is absurd and there is an even better reason.

Why absurd? Mostly because the Oxford English Dictionary traces the word back to 1935 in the Philippines:

“1935 Amer. Speech 10 79/1 Gook, anyone who speaks Spanish, particularly a Filipino.

“1947 N.Y. Herald Tribune 2 Apr. 28/6 The American troops‥don't like the Koreans—whom they prefer to call ‘Gooks’—and, in the main, they don't like Korea.”

Poetry. Poetry is essential stuff. Poetry makes us, takes us, helps us consider new places, new concepts, encourages us to revisit the condition of being human. Oh, it may make us laugh, may turn us from gloomy thoughts, but somehow, poetry takes us deep down into places we have never been have and perhaps never wanted to go, fills us with almost inexpressible joy or exposes us to a reality we might have preferred to avoid.

It is not always EASY because life is not always easy, and for the same reasons, it is not always pleasant; it does not fit on a Hallmark card. Weigl reminds me, whenever I read his poems, that sometimes the thickets of our lives are deep, dark and gloomy. Frost is right: “The woods ARE lovely / Dark and Deep” and, yes, “[we do] have promises to keep,” but Weigl forces us to realize that we should not ignore the Dark and Deep part of that beautiful poem, and that, yes, “The lie [hidden behind the beauty of the words] works only as long as it takes to speak / and the girl runs / only as far as the napalm allows.” I will not share more of Weigl’s poem except that “…Nothing / can change that, she is burned behind my eyes / and not your good love and not the rain-swept air / and not the jungle-green / pasture unfolding before us can deny it.”

I am, I suppose, avoiding writing about what happened between the two New Year’s days: ours and theirs. Nothing of what most people would consider “poetic” happened in those days. We worked, we slept, we taught at our little school, we hitched rides downtown or not. We were bored a whole lot. We kept up with the news. We read in the newspapers, saw on television, that General William C. Westmoreland thought the VC were in retreat, that they would be unable to mount any kind of sustained attack again. And we began to translate some odd messages.

Thursday, January 6, 2011

Just a Few Notes About Vietnam (Part 22)

There was simply no time to relax when we got back to the 330th and, at the same time, things seemed more and more boring. Most of the military action had settled down. A few ambushes here and there. I’m sure that was anything but boring for those being ambushed. We alerted the 4th ID to a few of them, briefed a colonel or two on what was happening around the Mang Yang Pass, taught at the school, walked or hitched downtown, read book after book (I finished the novels and poems of Thomas Hardy), dodged small red tornados. Christmas was coming soon and we had a truce for that day and a truce for the last day of January, the Lunar New Year.

But we did start getting some odd messages shortly after Christmas and those were not even encrypted. Someone announced that a provisional revolutionary government (PRG) had been established in An Khe, a shadow government for the RVN government in that town, a kind of government in waiting. Shortly after that, similar messages were sent north from Qui Nhon and Ban Me Thuot, from Dak To and Kon Tum, and then from hamlets and villages all over the Central Highlands. Frankly, we had no idea of what all that meant.

With hindsight, in February and March, we became pretty confident that the establishment (or apparent establishment) of all those PRGs (hamlet, village, city, province levels) had something to do with one of the stated goals the NLF and North Vietnam had for the upcoming Tet Offensive of 1968: to encourage an uprising of people from all over the southern region. If an uprising did occur, they might well have wanted an organization ready to step in. A moot point since no uprising occurred.

As for us: we kept slogging through messages pretty blindly. Other units were translating similar messages in their regions. If such shadow NLF governments were truly being established (and I don’t know that that actually happened because if it did those governments were ignored in 1975 after the tanks rolled into Saigon), then the NLF, in the months prior to Tet, had established a vast network of PRGs all over the South. As for me, I just worked. Allen just worked. Richard just worked and Jim and Will and the whole cast and crew in the Operations Tent on Engineer Hill. We all went to the office, put in our time, and got paid.

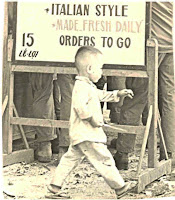

We worked. We played: on the Hill and downtown. I spent much of my downtown time chatting with kids on the dusty red streets of Pleiku, usually fairly close to the market on Le Loi Street and the intersection of two major highway: 14 And 19. I had purchased both a Yashika Mat 120 and an inexpensive Minolta SLR, 35mm camera. Allen Hallmark bought a Minolta 101, a really fine camera for its day. He became an exceptionally fine photographer, eventually becoming a newspaper photographer in Medford, Oregon.

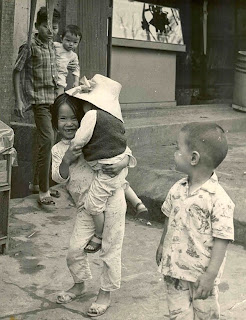

One of the things I liked about the Yashika was that it had one of those fake 90 degree lenses that allowed me to point the camera one direction and take a picture to the right. Almost all of the pictures in this blog were taken with that camera and most of those were of the children of Pleiku. These were the people, those children, who were most affected by the war, by our having gone to Vietnam. Most of them seemed cheerful in spite of everything, but their eyes could be hauntingly sad and hurt.

The Things We Leave Behind

War children. None of the ones in the photographs had known anything but war since they were born. Many of them were children of American soldiers and Vietnamese prostitutes, children with no futures.

Always the children. Chocolate bars

in World War II. Pictures with GIs.

Dirty, crying, doing what they have to.

We helped make them what they are.

They grow up in war zones, sacrifice

childhood, parents. Yet, somehow,

they survive. And the war, too: it

is always there: in their lips, their eyes.

We came to Vietnam by ship or airplane. Most of us put in a year, marked days off our short-timer's calendars, chalked up the experience to our youth, and left. We returned to whatever we had meant to be or had discovered we would become. The children? They remained, grew up, made whatever they could of what remained of their lives. We know the children of American GIs and Vietnamese prostitutes suffered terrible discrimination problems. The Vietnamese, after all, are no less racist than are we Americans.

It is much too easy to wash our hands of everything, to come up with some idea of this or that, some way to evade responsibility. “It was their war; we just went in to help.” “The dominoes were poised to fall.” “They shot at two of our ships.”

Excuses! We play huge board games with the lives of real people and real people are the game pieces. When an American soldier dies, a whole group of people (parents, relatives, friends) dies a little bit with him or her. When a Vietnamese, Iraqi, Afghani, Somali, Serb soldier dies, another group of people dies a little bit at the same time. John Donne said it best:

No man is an island entire of itself; every man

is a piece of the continent, a part of the main;

if a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe

is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as

well as any manner of thy friends or of thine

own were; any man's death diminishes me,

because I am involved in mankind.

And therefore never send to know for whom

the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)